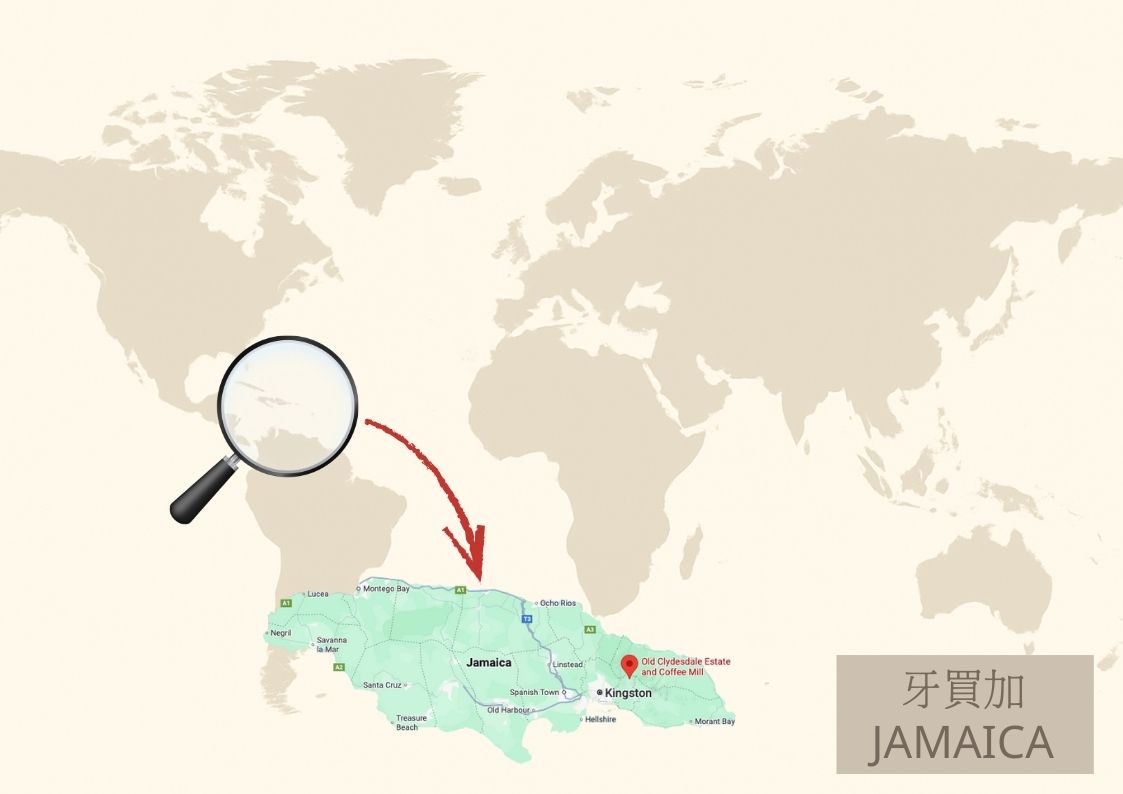

Coffee Origin : Jamaica

When people talk about Jamaican coffee, what often comes to mind first isn’t a trendy processing style, but a name shaped by law, institutions, and the market: Jamaica Blue Mountain®. Its value comes from a limited production area, steep mountain terrain that is hard to scale, and strict grading and export quality control. In the cup, it is typically known for a clean, gentle profile—fine sweetness, soft structure, and remarkably low harsh bitterness—an “elegant” style that feels composed rather than aggressive.

History & Institutions

Coffee arrived in Jamaica in the 18th century, and over time the cool mountain air and persistent mist of the Blue Mountains helped build its reputation. This history is not simply a timeline of growing fame—it is also the story of a regulatory framework that made “Blue Mountain” a name that can be identified, protected, and trusted.

On the institutional side, Jamaica’s coffee sector has long relied on official standards and certification. The Coffee Industry Board of Jamaica (CIBOJ) played a major role historically in industry development and quality oversight. Later, responsibilities were consolidated under JACRA (Jamaica Agricultural Commodities Regulatory Authority), which supports regulation, standardization, quality assurance, and certification services. The reason “Blue Mountain” remains globally recognizable and legally defensible is precisely because it is anchored in this system of certification and authorization.

Terroir & Geography

The Blue Mountains rise in eastern Jamaica, with steep slopes, frequent cloud cover, cool temperatures, and abundant rainfall. Soils are generally well-drained, allowing coffee trees to mature in conditions that are humid but less prone to waterlogging. These factors often translate into brighter clarity, more refined sweetness, and a smooth mouthfeel—key foundations of the classic Blue Mountain character.

Shade-grown systems are also common. The mix of mountain tree cover and companion crops affects ripening pace and cup style, while also supporting moisture retention, reduced heat stress, and long-term soil health—part of the “slow maturity” backbone behind the region’s gentle elegance.

Varieties & Agronomy

The backbone variety in Jamaica is Arabica Typica, often considered the structural core of the Blue Mountain profile. Typica tends to express delicate aromatics, a soft texture, and clean sweetness—well aligned with Blue Mountain’s long-standing pursuit of balance.

While other varieties may appear in limited trials or niche lots, the mainstream language of Blue Mountain coffee is still built around Typica: consistency, cleanliness, and refined texture are the central promises that define the category.

Processing in Jamaica

Classic Blue Mountain coffees are most commonly washed. Harvesting often emphasizes selective picking—only ripe cherries—followed by pulping, fermentation, washing, and careful drying. Depending on conditions, drying can combine sun-drying with mechanical support to stabilize moisture content. The coffee then rests, is hulled, graded by density and screen size, and finished with detailed hand-sorting to push uniformity to a very high level.

One unmistakably Jamaican detail is export packaging. Blue Mountain has historically been associated with wooden barrels, which function both as an iconic market symbol and as part of the traditional supply chain culture. In other words, “Blue Mountain” is not only a cup profile—it also represents an organized, institutionalized origin system.

Tasting Guide

Top-quality Blue Mountain typically doesn’t aim for explosive fruit acidity or heavy fermentation notes. Instead, it stands out for balance, cleanliness, and a silky finish. Sweetness often reads as gentle cane sugar or caramel; acidity is usually soft and citrus-peel-like rather than sharp; aromatics may show light florals, cocoa nuance, and a subtle creamy tone. The aftertaste is clean, with very low astringency or harsh bitterness.

This makes Blue Mountain especially suitable for drinkers who want something “everyday friendly” without fatigue. It doesn’t demand attention—it earns it quietly, through polish and clarity.

The Legally Defined Blue Mountain Growing Area

“Blue Mountain” is not a casual label for high altitude coffee; it is a legally and institutionally defined geographic name. Coffee must come from the designated area and comply with certification standards to be marketed as “Blue Mountain.” That framework is a core reason the category maintains strong recognition internationally while reducing confusion and misuse.

In general market descriptions, the Blue Mountain area is associated with specific mountain zones spanning parishes such as Saint Andrew, Saint Thomas, Portland, and Saint Mary, with boundaries described more precisely through defined geographic markers. For consumers, the key takeaway is simple: Blue Mountain isn’t “self-declared”—it is traceable and verifiable.

Estate Highlights: Amber Estate No.1 | Clydesdale Estate No.1 | Silver Hill Estate No.1

Amber Estate No.1 is commonly presented as a Typica, washed Blue Mountain-style lot, often emphasizing cleanliness, sweetness, and fine aromatics. Typical tasting language leans toward citrus, maple or syrupy sweetness, a smooth texture, and a tidy finish. If you want a classic Blue Mountain profile with a touch more aromatic lift, Amber is often a dependable choice.

Clydesdale Estate No.1 is widely recognized as a representative Blue Mountain estate. Market descriptions frequently highlight roundness and balance, with notes that lean into nuts, malt-like sweetness, dark chocolate nuance, and a creamy, steady body. It suits drinkers who prefer a fuller, more grounded sweetness with very gentle acidity.

Silver Hill Estate No.1 is also often described as Typica and washed, with tasting notes commonly pointing to brown sugar, caramel, cashew-like nut tones, a light floral base, and a clean close. If your preference is for clearly defined sweetness and delicate aromatics in a refined frame, Silver Hill often fits that direction well.

Harvest & Seasonality

Blue Mountain harvest is often described in two broad periods: one beginning in late summer or early autumn and extending through year-end into early the next year; and another beginning later in the first quarter and running into late spring or early summer. This rhythm can produce subtle differences across lots—even within the same estate and year—such as variations in sweetness definition, citrus brightness, or body weight.

For retail and brewing enjoyment, arrival timing and freshness matter. Blue Mountain isn’t necessarily about the loudest aromatics; it is about clean detail—and that value can fade more noticeably if storage and freshness are not well managed.

Grading & QC

The Blue Mountain system commonly includes grades such as No.1, No.2, No.3, and Peaberry, with “Select” often seen as a market grouping of multiple grades. Behind these labels sits a framework focused on screen size, density, moisture targets, defect control, and rigorous sorting—supported by certification practices that aim for consistent, predictable quality.

This is a major reason Blue Mountain has long been seen as “low-risk” in the cup: its value comes less from novelty and more from disciplined standards and traceability.

Sustainability & Community

Jamaica’s Blue Mountain supply structure often combines many smallholders with a smaller number of larger estates. Mountain farming is costly and labor-intensive—steep terrain makes harvesting and transport harder—so pricing and regulation are not just market positioning; they directly affect livelihoods and whether farmers can sustainably remain in the coffee economy.

At the same time, shade management, soil care, and water stewardship are essential for long-term resilience in these landscapes. When Blue Mountain is treated as a premium and trusted origin, it also implies a social contract: verified quality and clear standards should translate into fairer returns and a more stable production ecosystem.

Future Challenges

Jamaica’s coffee challenge is rarely “how to produce more,” but rather how to maintain quality and authenticity within limited output. On one side is the ongoing pressure of mislabeling and imitation—making certification discipline more important than ever. On the other side are structural realities: climate volatility, labor costs, the difficulty of mountain cultivation, and whether younger generations will choose to remain in agriculture.

In short, the future of Blue Mountain won’t be secured by being “louder,” but by being clearer—clearer standards, clearer boundaries, and clearer quality logic—so it can continue to hold its distinct place in the specialty world: quiet, elegant, and credible.